Starting point

Many children around the world are currently failing to achieve the WHO recommended levels of physical activity and are increasingly experiencing physical and mental health symptoms. Physical activity offers many benefits for children’s physical and mental health and cognitive development. Increasingly, the latter spend their leisure time indoors and under supervision, rather than moving independently outdoors. The dominance of motorized traffic, lack of (child-friendly) infrastructure, and lack of open/green spaces reinforce this effect of “domestication.” Parents limit their children’s range of motion due to perceived risks in public spaces, leading to lower levels of physical activity. This is reflected in a decline in active forms of mobility (walking, biking/scootering) on school and recreational trips. To reverse these trends, many approaches are needed: including deeper insights into mechanisms of behavior change, perceptions of the built environment, mobility-related choices, and the impact on children’s well-being; the influence of the social environment, technologies, or policies on independent mobility; the ways in which the environment facilitates or constrains children’s active and independent mobility.

Project overview and goals

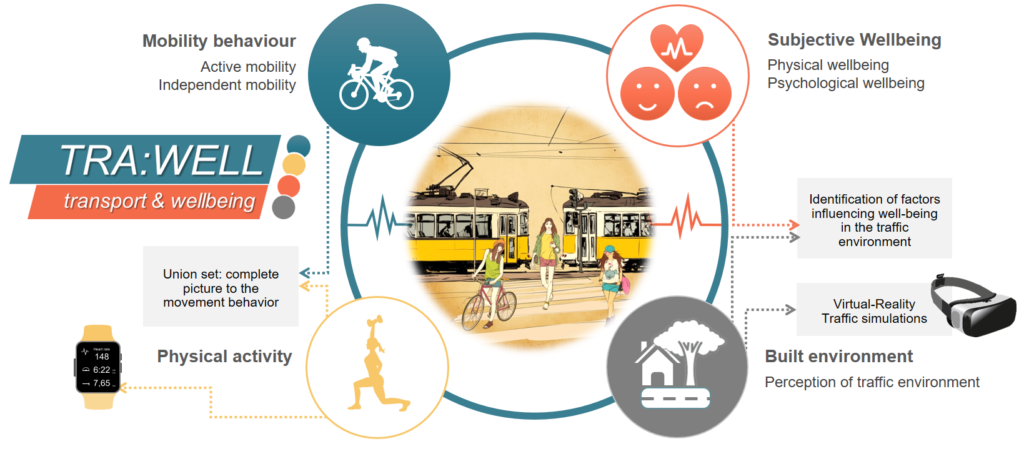

At its core, the TRA:WELL project investigates how active and independent mobility is related to children’s well-being (Figure 1). In doing so, the subjective perception of the built environment is analyzed and a child-centered perspective is elaborated on how urban environments can promote child-friendly mobility. The study takes into account the overall physical activity behavior and shows how active forms of mobility can contribute to the fulfillment of physical activity recommendations.

Students learn about scientific methods in whose (further) development they are actively involved and which describe the complexity of mobility-related decisions from their point of view. The project results provide important arguments in the context of child-friendly mobility for scientists, decision-makers and parents and give deeper insight into the reality of children’s lives – not only into their mobility and movement behavior, but also into the well-being related to mobility and public spaces, which is more difficult to capture. From a scientific point of view, substantial insights are gained in a new research field and further usable data and methods are generated. The project contributes significantly to the interdisciplinary consideration of transport/mobility & health and thus to the “Health in all Policies” approach. In addition to the political significance that can be derived from this, children learn about another important aspect of research, namely the scientific discourse with the international council of experts. TRA:WELL also has high practical relevance when it comes to designing child-friendly traffic areas.

The project’s target group is primarily students aged 10-14. The project aims to strengthen self-, subject-, methodological- and social competencies and to awaken students’ interest in research by actively involving them in the project. These acquired competencies will benefit them in the course of their further school career, for example for school projects or pupils’ pre-scientific theses. The topic of mobility at the interface between social sciences, environment and technology/engineering offers a good insight into the broad world of science.

Project Schedule

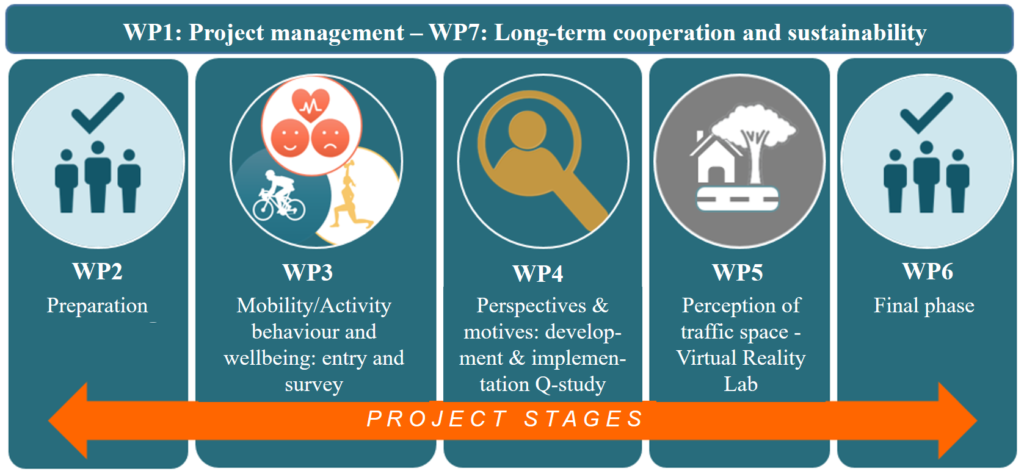

For the project TRA:WELL, 7 work packages are defined, which are processed over a project duration of 26 months and are closely interlinked. In addition to the project management (WP1) and the planning and implementation of the long-term cooperation and sustainability (WP7), the project is carried out in 5 main phases (Figure 2). After a preparation, the intensive cooperation with the students will take place over 4 school semesters in the school years 2022/23 & 2023/24. The project has connecting points to different school subjects, which are agreed with the partner schools. In the course of the project management (WP1) the overall coordination between the actors takes place. The project coordinator has many years of experience in the management of school projects. Quality assurance in WP1 includes, among other things, that all interactive sections contain evaluation parts (regarding comprehensibility, motivation, learning effect, fulfillment of expectations) in order to keep TRA:WELL adaptable and responsive and to ensure high data quality. Based on the communication principles of the project, the strategy is created and fed back with the actors in the project. A communication interface between educators, students and researchers will be established via the project homepage (e.g. weblog, e-mail distribution list). Dissemination and reporting will be part of this WP. The participation of the expert advisory board (information and exchange) is also part of WP1.

In the preparatory phase (WP2), the synthesis of current literature with regard to the relationship between mobility and well-being is carried out, as this is a currently unfolding field of research[2]. In addition, preliminary work for the survey of mobility/movement behavior and well-being (WP3) and the didactic preparation for the integration of the Q-method in the classroom (WP4) are carried out. In WP3 (Mobility/movement behavior & well-being: entry & survey) the entry workshop takes place, which includes a short introduction to transport and mobility and in which the research question is discussed together. Students are given the task of further developing survey instruments in the area of mobility behavior with regard to well-being and independent mobility (chapter on research methods). The starting material will be travel diaries created by students in the Sparkling Science project “UNTERWEGS” (2012-2014). Ideas are incorporated and presented in the methods workshop, which also serves to familiarize students with “passive-tracking” methods for surveying movement behavior. After the students have completed the survey, the data will be processed and analyzed by the researchers. In WP4 Perspectives & Motives: Development & Implementation Q-Study, students go in search of motives and self-concepts underlying their mobility/movement behavior. The Q-Study aims to identify common perspectives that people have regarding a particular behavior (Danielson, 2009; Zabala et al., 2018). This involves identifying socio-psychological factors influencing perceptions of the environment that influence mobility-related decisions. The importance of habit, freedom of choice, well-being, perception of safety, etc. are reflected. Initial factors for the perception of the environment are thus identified and reflected. Starting point are the results of the quantitative survey in WP3, which will be discussed in a workshop. Together with the researchers, students develop statements as a basis for the Q-sort. The Q-Sort is implemented online and tested in parallel classes; students present the Q-Sort. In order to also learn about adult motives and reflect on similarities/differences to their own motives, students conduct interviews with adult caregivers. As a result of the collected individual Q-Sorts, mobility types can be derived, i.e. similar or different perspectives. In an online event, which could take place e.g. on Gather Town, students learn about the first results of the Q-study and report on experiences from the interviews with adults. Parents also participate in the event. The results of the reflection will be used for further analysis by the research team. WP5 is dedicated to the perception of the traffic space and the VR (virtual reality) environment. Many factors play a role in whether children feel comfortable in the traffic space. In the workshop “Safety – Perceiving”, students are introduced to factors influencing a safe stay in traffic space. Under the guidance of traffic psychology and pedagogy trainers, a catalog is jointly developed that lists criteria for a safe design of the traffic area. Interactive workshop elements are used. The output is a traffic space logbook containing at least one criterion of personal safety, traffic safety, infrastructural safety and social safety in traffic space. The logbook can be displayed and disseminated to the public in the context of postings or photos on social platforms, such as Instagram. The identified factors or logbook will serve as the basis for constructing virtual environments that students will experience in a field trip to the Institute of Transportation’s VR Lab. Reactions to different scenarios are measured and analyzed in terms of perception of safety, comfort, etc. The results can be used to derive criteria for characterizing child-friendly (traffic) environments. In the final phase (WP6), a conference is organized by students with the support of scientists and educators, which includes scientific formats. Young researchers give keynote speeches themselves, guide through poster or video presentations, experience keynote speeches in the lecture hall and participate in parallel sessions on topics they have a say in (e.g. well-being and everyday mobility, visions of livable cities, participation of children in planning processes).

The highlight of the conference is a panel discussion in which experts from the advisory board, political representatives and students discuss. A jointly written manifesto for active, independent and safe mobility of children and young people is read out. The conference serves not only as a conclusion of the project from the students’ point of view, but also for networking across educational institutions and for collecting visions from the students’ life worlds. Other elements of the final phase are the detailed analysis of the data material (quantitative survey, Q-Sort, VR) in relation to the research questions and report writing. A task in the implementation of a long-term cooperation (WP7 – Long-term Cooperation & Sustainability) is the development of the teaching unit “Active Mobility & Well-being”. This will be designed and tested with educators in the project and will be freely available later. The Q-Sort will be available (possibly as part of the teaching unit) as a teaching element for self-reflection on mobility behavior. WP7 also includes the further development (+testing) of the created virtual environments; schools will be invited for field trips (VR lab) after the project end. Younger age groups will be involved e.g. via the children’s university. In WP7, the preparation of an (international) cooperation/follow-up project will be explored with the expert advisory board.

Methods

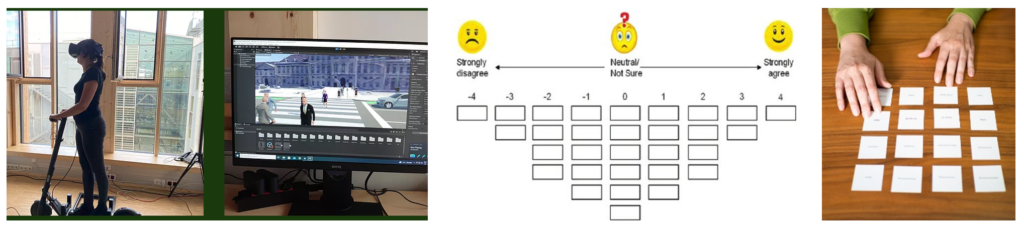

The research questions in the TRA:WELL project will be addressed using quantitative and qualitative empirical methods. In the first phase of the project, a written survey will be conducted, which will use route and activity diaries as data collection instruments. Existing questionnaires suitable for young people will be adapted by students in order to survey activities, freedom of choice and well-being in addition to mobility behavior (Figure 3). The survey will be conducted over one week to generate data on routes to school, leisure routines (e.g., training at a sports club), or activities on weekdays and weekends. This survey period allows the profiles to be correlated with weekly physical activity targets (WHO) for children. Garmin Vivosmart 3 activity trackers are used to effectively record intensity and duration of physical activity during the survey period. The devices are worn on the wrist and record heart rates, accelerations, stress patterns and sleep stages, among other things. Data from pathway diaries and measurements are merged to create a comprehensive picture of children’s activities or behaviors over the course of a week.

In the next project phase, students will apply a method at the interface of quantitative and qualitative procedures to describe the complexity of individual, mobility-related decisions. The results of the survey from the first project phase form the basis for this. The Q-method is used to collect socio-psychological factors such as attitudes and value orientations. The respondents then classify these statements into a Q-set (Figure 4).

The Q-sets are analyzed using software to derive mobility types. Each mobility type combines people who have sorted statements similarly. It is not about the sorting itself, but only about the comparison of similar or different sortings, opinion patterns (Danielson, 2009). Therefore, this method also works well for students’ reflection with (motives for) their movement/mobility behavior (self-concepts). The method, which originated in the English-speaking world, comes from psychology (Müller & Kals, 2004) and is now used in a number of social research topics such as health (Jacobson, 1987), media & market research, and social psychology (Block, 1991; Müller & Kals, 2004). On the topic of mobility, the Q method has been used only sporadically (e.g., Brůhová et al., 2020; Cools et al., 2009; Hickman & Vecia, 2016). Studies show that for the target group of children and adolescents the Q-method is very suitable, because it opens the possibility for them to take a stand “in a participatory, non-threatening, unobtrusive way” (Owens, 2016, p. 236). In the TRA:WELL project, students design the statements themselves with the support of the researchers; these can be whole sentences, individual words, pictures, or figures. Based on their own behavior, they find determinants for mobility-related decisions in group discussions and self-reflection. The method thus has the advantage that reflection and thus a learning process already takes place in the development of the statements, i.e. the preparation of the measurement instrument. In the third project phase, virtual reality technologies of the Institute of Transportation are used (Figure 4). Among other things, these enable the observation of dynamic behavior when driving an e-scooter in response to changes in the structural, urban infrastructure. Scenarios can include, for example, different widths of bike lanes or distances to car traffic. In this context, the subjective perception (comfort, risk, safety) is surveyed on a scenario-specific basis via the driving behavior, which can be directly related to the acceptance of active mobility alternatives (merging data from survey and Q-Sort). The parallel use of eye & activity trackers also provides information on stressful traffic situations. The results will be used as a basis for deriving criteria to characterize child-friendly (traffic) environments or policy recommendations.

References

- Block, J., 1991. Self-Esteem through Time: Gender Similarities and Differences. In Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development. Seattle: University of California, Berkeley.

- Brůhová Foltýnová, H., Vejchodská, E., Rybová, K., Květoň, V., 2020. Sustainable urban mobility: One definition, different stakeholders’ opinions. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 87, 102465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2020.102465

- Cools, M., Moons, E., Janssens, B., Wets, G., 2009. Shifting towards environment-friendly modes: profiling travelers using Q-methodology. Transportation 36, 437–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-009-9206-z

- Danielson, Stentor. 2009. Q Method and Surveys: Three Ways to Combine Q and R. Field Methods 21 (3): 219-237.

- Hackl, B., 2020. Die Q-Methode, https://fhstpmedien.wordpress.com/2020/11/21/die-q-methode/ (29.09.2021).

- Hickman, R., Vecia, G., 2016. Discourses, Travel Behaviour and the “Last Mile” in London. Built Environment 42, 539–553. https://doi.org/10.2148/benv.42.4.539

- Jacobson, S. W., 1987. “Strong” Objectivity and the Use of Q-Methodology in Cross-Cultural Research, 9(2), pp. 183–205. http://doi.org/10.1177/07399863870092005

- Müller, F. H. and Kals, E., 2004. Die Q-Methode. Ein innovatives Verfahren zur Erhebung subjektiver Einstellungen & Meinungen. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung, 5(2), pp. 1–15.

- Owens, Larry (2016). The use of Q sort methodology in research with teenagers. In Jess Prior & Jo Van Herwegen (Eds.), Practical research with children (pp. 228-245). London: Routledge.

- Spehr, Michael, 2018. Wenn der Sauerstoff fehlt und die Atmung aussetzt. FAZ. URL: https://www.faz.net/ aktuell/technik-motor/digital/garmin-sportarmband-vivosmart-4-im-test-15908575.html (31.10.21)

- Stark, J., Skok, M., Müller, C., Meschik, M, 2022. Activities and Active Mobility of Children – at the Interface of Travel Behavior and Health Research. 12th International Conference on Transport Survey Methods, Praia de Porto Novo, Maceira, MAR 20-25, 2022] In: ISCTSC, 12th International Conference on Transport Survey Methods – Program

- Westbrook, Jenna & McIntosh, Catriona & Sheldrick, Russell & Surr, Claire & Hare, Dougal., 2013. Validity of Dementia Care Mapping on a neuro-rehabilitation ward: Q-methodology with staff and patients. Disability and rehabilitation. 35. 10.3109/09638288.2012.748839.

- Zabala, A., C. Sandbrook, and N. Mukherjee. 2018. When and how to use Q methodology to understand perspectives in conservation research. Conservation Biology 32 (5): 1185-1194.